Kelela: The white people are taking our space in front of the stage

Kelela: The white people are taking our space in front of the stage

Her debut is undoubtedly one of the best R&B albums of the year. In an interview, KELELA explains why her music is dedicated to black women and why you should admit more often that you don't understand something

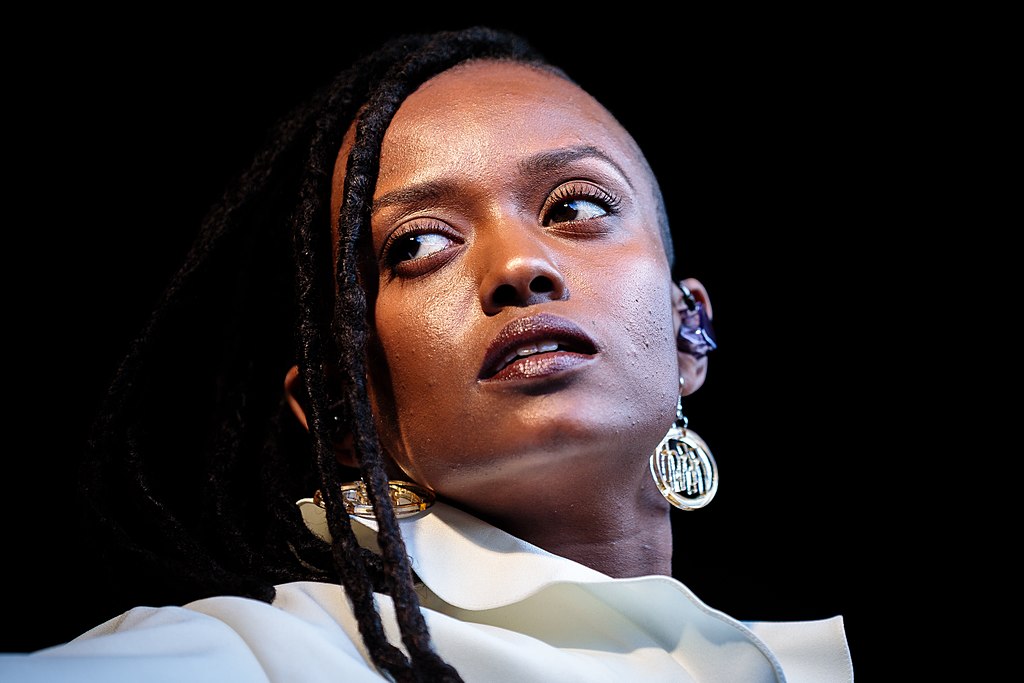

(Image: Tore Sætre, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

That's what you call presence: Kelela sits upright on the front edge of a soft sofa, her spine straight, her hands resting on her knees, her head slightly bent forward. Despite barely four hours of sleep, the 34-year-old is highly focused and ready to teach us a lesson in humility. "I don't think white people really understand my art," she says, clearing her throat. "Don't get me wrong, I want everyone to enjoy my music, but I also want them to know that I didn't make these songs for them, but primarily for black women like me."

For almost five years, young, often black musicians such as Solange, Bosco, Princess Nokia, ABRA and FKA twigs have been redefining R&B by subverting the polished pop sound of the mainstream with avant-garde sounds and a sense of political mission. "Without knowing each other, we all had similar experiences and combined similar influences to create something new. It was somehow in the air," says Kelela, who has been one of the great hopes of this new wave since her mixtape "Cut 4 Me" in 2013 and at the latest since her EP "Hallucinogen" released in 2015. Like her colleagues, Kelela has designed herself and her music as a fully aestheticized work of art. And like them, the daughter of Ethiopian parents, in her proud stance as a "person of color", stands for a new self-confidence among non-whites who are seeking to join forces around the world to fight "white supremacy" and "white privilege".

Fight against “white privileges”

Kelela spent most of her childhood and youth in Gaithersburg, Maryland, the most multicultural city in the United States according to a study published in 2016. Although her neighborhood consisted mainly of people with an immigrant background, she was exposed to a strong white influence from an early age. "I am the product of an anti-segregation program called 'busing,'" explains Kelela, energetically throwing her dreadlocks over the clean-shaven left side of her head. "Instead of attending the school closest to our home, my friends and I were bused to a white area every day." The measure to ethnically mix school children, which was implemented by the US government since the 1970s and abolished in the 1990s, was in reality just masked racism, believes the former sociology student, whose full name is Kelela Mizanekristos.

"At home, I was surrounded by other people of color, while the lessons at school were tailored to white children. History, social studies - nothing helped me find a place in this society. Many black young people take a deep breath once they have left this period of white ignorance behind them. And then they gather their own information to understand how this inequality could really have happened."

Minority within a minority

In her music, Kelela wants to depict the "complex and convoluted" reality of black women's lives, a minority within a minority. By grounding radio-friendly R&B with jagged electronics and capsizing sensual vocal melodies that flow over it with dragged-out beats, schizophrenic moments full of warm comfort and cold alienation arise. Her debut album, aptly titled "Take Me Apart", which is released on the London intelligent dance music label Warp, can be broken down into hip hop, grime, house and trap elements, but also contains elements of gospel, soul and jazz. Her main goal is to write classic songs that work on a piano alone, "so that someone like Carole King would say: 'Good song!'" explains Kelela, giggling. "All the crazy stuff on the sound level comes later. From a global pop music perspective, we're reshuffling the cards with 'Take Me Apart'. Let's see what happens."

The self-confident "we" that Kelela brought together as executive producer for her debut in the studio includes a handful of producer friends from the Los Angeles-based urban underground label Fade To Mind, with whom she already released her first mixtape as a collaboration. But outstanding loners such as the Venezuelan ambient surrealist Arca and the Canadian neo-jazz jack-of-all-trades Mocky also worked on "Take Me Apart". Although her music conveys a "black perspective", Kelela's taste in music is diverse. Since her teenage years, she has admired Björk and Tracy Chapman. Most recently, she has made guest appearances on albums by Danny Brown and the Gorillaz. R&B singers of the 90s were decisive for the aesthetics of her debut and her current self-image as an artist. "Black women like Mary J. Blige, Lil' Kim, Faith Evans and Janet Jackson who defined the decade with their style and attitude."

The video for "LMK", the pulsating first single from "Take Me Apart", is a tribute to this time, the retrofication of which has so far hardly progressed. It was shot by Andrew Thomas Huang, Björk's long-time director. In it, Kelela dances through neon-lit club corridors in a platinum blonde Lil' Kim wig, surrounded by her gang, who radiate the invincible sisterly gesture of TLC and Beyoncé's former girl group, Destiny's Child, with their synchronized hip swings. Kelela is close friends with Beyoncé's younger sister, Solange, and on her last album, "A Seat At The Table", they sing the chorus of the solemn self-empowerment piece "Scales" together.

"With 'A Seat At The Table', Solange managed to create a community in a wonderful way. She really invited people to a table by saying: This is the message - do you want to share it with us? There isn't a black artist in the world with a microphone in their hand who hasn't taken this opportunity. Because we all know experiences like the one Solange sings about in 'Don't Touch My Hair'."

Against cultural appropriation

However, Kelela feels that the fact that "A Seat At The Table", written and arranged by Solange alone, was celebrated by critics around the world as a black music milestone is a mixed blessing. "Magazines sound progressive when they celebrate 'A Seat At The Table'. But the fact that they are reviewing it is ironically in line with the cultural appropriation that Solange talks about on the album. Many white people love these songs, but they have not understood the second level, otherwise the lyrics in them would promote a certain humility and restraint," says Kelela. Her previously rather gentle, calming tone has become sharper and faster on the subject. "You could follow this very well on Twitter during Solange's festival appearances. Black women wrote, among other things: 'The white people are taking our place in front of the stage. Don't they know that this is about us and our cause?' A lot of white people say things like, I've read Malcolm X, I've heard 'A Seat At The Table,' I get it! And then they brush it off."

The white people take our place in front of the stage

Kelela believes that no one else is imitated and appropriated as often as black women. At the same time, no one is underestimated as much as she is. "Take the surprise that Solange caused. Black women are constantly confronted with this surprise. I would like to shout at them: Why do you assume that I can't be a genius?!" Then Kelela sinks backwards into the sofa cushions. For the first time during the conversation, her body tension eases, as if she has run out of breath. Perhaps because she has already gotten worked up about all this too many times.

What would she want from her white listeners? Kelela picks up the thread again, emphatically and patiently, as if she were explaining something all too obvious to a child: "You have to be constantly aware of things like racism and sexism - not just claim to have understood something and then put it aside. The humility of not understanding something leads to much better results than this feeling of 'Yes, I got it'. As a white person, you can listen carefully to my songs and love them. But what counts is what comes after. What decisions do you make now, has a sensitivity arisen in you? These are the big questions. And that is also the starting point of my music."