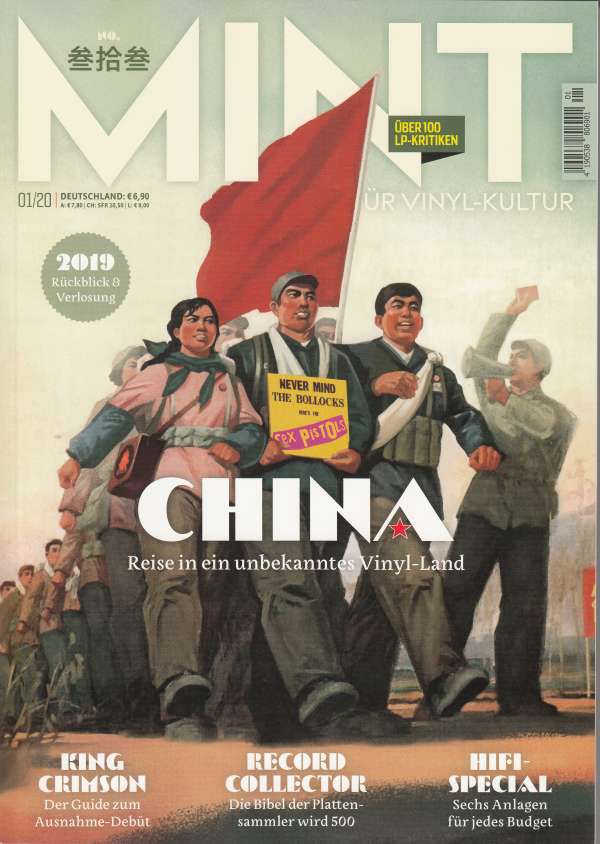

Vinyl in China – FROM TRASH TO TREASURE

In spring 2018, China, for years the world's largest importer of waste, announced that it would no longer accept waste from other industrialized nations: the country is now rich enough to no longer be dependent on raw materials from recycling. Only a few people know that this also marks the end of a piece of modern Chinese music history. After all, China's young pop culture literally grew out of the manure.

The containers that docked in the Pearl River Delta and other coasts for decades not only transported waste from prosperity for the "workbench of the world" - recyclable copper, iron and paper - but also other treasures that China's youth in particular craved: music. Large record companies from the West and Japan shipped their unsold recordings to China by the ton to be disposed of as residual waste to recycling companies. But instead of ending up in the machines that were supposed to melt and granulate the plastic, parts of it found their way into the heart of a country that, after years of isolation, dramatic crises and ideological trench warfare, finally seemed ready to open itself up to the world.

The year is 1992. Three years after the suppression of student protests in Beijing's Tiananmen Square, the 87-year-old head of state Deng Xiaoping travels through southern China for the last time to preach the party's new core goals in the special economic zones: money, growth and power. "Getting rich is glorious" is the motto with which the reformer wants to stimulate the private sector again after years of state control. The words of China's gray eminence bear fruit: "The once totalitarian-controlled masses have transformed into an army of entrepreneurs, traders and consumers," wrote the "Spiegel" in 1993. And indeed: within a year, the national product grows by 12.8 percent, and industrial production even by 21 percent - a world record. As if the planned economy had never existed. It is no longer possible to trace whether it was dock workers, garbage collectors or music fans who first saw the business in the discarded audio media in this atmosphere of liberalization. What is certain, however, is that CDs, cassettes and, in smaller quantities, records soon appeared across the country in underground shops, electronics markets and cardboard boxes in front of universities. For many young Chinese, it was as if they had suddenly struck gold in their own backyard.

Today, in China, they are referred to as the "Dakou" generation. "Dakou" means something like "saw marks" because the covers of surplus records were often scored by machine before transport and sometimes even punched with a hole to prevent them from being resold. This did not bother the music-hungry youth, who could finally escape the sweet and conformist pop of the mainstream by taking them to the rubbish dump. Firstly, the records were usually still listenable and secondly, there were hardly any alternatives. The Internet was not yet an issue. Imports from abroad, from Taiwan or Hong Kong, were too expensive for most people, and the records from the West approved by the state import-export authority were limited to big stars like Mariah Carey or Michael Jackson.

"Whatever was offered to you became the soundtrack of your life," Zhang Youdai recalls of those lean years. The 52-year-old is something like the "Chinese John Peel" in his home country. Since the early 1990s, he has been presenting new and old music from all over the world in his radio shows and offering a platform to up-and-coming Chinese artists, even if they only have a demo to show. During our interview in Zhang's bar "Cloud 9" in northwest Beijing, young guests repeatedly address him as "Zhang Laoshi" - "Teacher Zhang". When Zhang started collecting music in the mid-1980s, the mass market was firmly in the hands of Chinese pop stars. Rock music was still a novelty. The only star was called Cui Jian, a kind of Dylan figure who towered above everything else, but also lost revolutionary traction with the suppression of student protests after 1989. Alternative music in China only began to differentiate itself in the 90s thanks to the garbage dump goods that suddenly appeared everywhere, which also suddenly broadened the horizons of many Chinese musicians. Indie bands such as Carsick Cars, New Pants and Hang On The Box were inspired by "Dakous", which the dealers usually bought by the kilo without sifting through them first. Zhang remembers that the recordings were usually completely intact, especially on the floor of the containers. "You never knew what you were going to get! Sometimes a ship would only have heavy metal on it, sometimes only experimental music. It also happened that the shelves were suddenly full of the same album!” The arbitrary shortage had the nice side effect that some bands that were at most one-hit wonders in the West, or albums that we consider to be weak late works, still hold a special place in the hearts of the Chinese “Dakou” generation to this day, such as the American indie rockers Tripping Daisy or the 1996 album “Generation Swine” by Mötley Crüe, to name just two examples. Of course, none of this ever reached the artists. In the end, it was nothing more than residual waste. “Sometimes a single box was a real gold mine. But often there wasn't a single good piece in it,” remembers Xiao Bing. The 28-year-old runs a label and a record store in Shanghai. The hip hop lover also bought her first records in "Dakou" shops, quite randomly, to learn how to scratch with vinyl. "Many of the dealers were normal Chinese, often older people. Most of them knew nothing about music, but understood all the more about supply and demand," she remembers. The more popular an artist was, the higher the price was often. Customers acquired their knowledge from fanzines or by talking to other music fans. "We often put on a poker face when we discovered a particularly good record. We couldn't let it show so that the dealer didn't spontaneously demand more money."

With the advent of the internet, torrent platforms and streaming services, most record shops in China disappeared from the scene, both mainstream shops with mass-produced goods and pure "Dakou" shops. The few narrow rows of shops that are still left have mostly switched to copied DVDs, but sometimes still sell copies of the scratched contraband. "Today, the containers with 'Dakous' mainly go to India or Myanmar," says Xiao Bing. Wages there are now cheaper than in China, and it is still worthwhile for the recycling industry to extract the raw materials from the often highly environmentally harmful waste. "That's why you hardly find good 'Dakous' in China anymore. What collectors haven't bought up yet is often just garbage," laughs Xiao Bing.

The influence of the "Dakou" generation on China's alternative music scene can hardly be underestimated. Some dealers and customers from back then have now set up professional record stores, with a Discogs catalog and a well-informed customer base. They sell old treasures from the bin, but also back catalogs of local artists and imports. But even these "conventional" stores in our sense do not operate entirely legally here to this day.

As "cultural goods," sound recordings from abroad are subject to strict import laws in China. The government wants to control exactly what content comes into the country. In theory, nothing can be published and sold without a state license. And that is not so easy to get. "Only the government has the right to issue licenses. So if you want to sell sound recordings, in theory you can only choose from the range that the relevant authorities have already approved. From abroad, these are mainly big pop stars like Whitney Houston," says Xiao Bing.

Today, there are just 10 to 20 record stores in the whole of China that specialize in vinyl. Most of them only sell imported goods in very small quantities. "You have to give the local police in the neighborhood a little money. Then you won't have any problems," explains Zhang Youdai with a wink. Most record stores have such agreements, confirms Xiao Bing. She herself circumvents the system of "small favors" by setting up her shop in a private apartment on the eighth floor of a residential complex. Only a tiny sign on the door indicates that this is more than just a place to live. "If someone comes and says, 'you're not allowed to sell foreign music here,' I can say that it's just my private collection. Nobody can forbid me from selling my personal second-hand records."

Having a record store in China means finding loopholes and moving confidently in grey areas. It's inconvenient, but it also creates a sense of solidarity and often a family atmosphere: At Xiao Bing, customers can lounge on beanbags like they're at a friend's house, listen to records, drink coffee, smoke a cigarette on the terrace with a view of the city, or read the in-house music newspaper "Changpian Richang," which Xiao and her business partner publish four times a year. "You live by word of mouth," says Xiao. "We have to keep it as small as possible." Unfortunately, that also means having to live in constant uncertainty: every day, what you've painstakingly built up could be destroyed by a raid. "We want to be legal, but that's not so easy in China," says Xiao. To prevent a failure, she and her partner have positioned themselves broadly. They not only sell records, but also help local artists get their music to customers in Europe, the USA and Asia. "There are hardly any international distributors for Chinese musicians. That's why many people come to us." The pair also run a service agency that arranges DJs and advises media companies on background music. With their own label "Eating Music", they have also been producing their own records for some time - "as legally as possible", as Xiao Bing emphasises. "We simply try to get a state license for everything." To do this, they have to submit the lyrics of every song they want to release to the cultural authority and, if they are in English, translate them into Chinese as well. "In fact, most of our releases are instrumental hip hop, ambient or electronic tracks, so they have no lyrics at all or very few. That makes it easier to get a license." If the titles go through, they get a catalogue number. This costs around 2000 renminbi (the equivalent of 255 euros) per album, and 500 (just under 64 euros) for a single track. Without foresight and a sense of business, it's easy to miscalculate. "You have to be pretty sure how much you can sell before you apply for a license, otherwise it will be uneconomical." In addition, depending on the political climate or upcoming major events, the checks may be stricter than usual. This happened before the 2008 Olympic Games, for example, when punk rock and similarly aggressive underground music was temporarily barely licensed. In times like these, the authorities don't want to take responsibility. "We all know the problems with cultural control," says Xiao Bing and sighs. "The government wants to control your thoughts. But of course it's not that simple. That's why I think the whole licensing thing is mainly about money: the stricter the system, the more the authorities can earn."

When it comes to music consumption, China has now moved into the digital age more comprehensively than many other countries. Streaming services such as Tencent Music, NetEase Music and Xiami dominate the mainstream. But vinyl has also become a growing niche market in the People's Republic. "In the past, China was always ten years behind the West. However, the vinyl hype reached us only with a slight delay," explains Zhang Youdai. The number of vinyl collectors is growing. And not just in the indie sector. Jazz and classical albums are considered status symbols by many nouveau riche global citizens, which are brought out like fine wine on special occasions.

"For most people, vinyl is primarily a lifestyle product, a collector's item that you can use to show how individual you are," says Zhang. "Most vinyl buyers don't even have a record player at home. I can't stand that." No wonder: Zhang had to painstakingly buy his collection over many years. He got a taste for it in the 90s, during a stay in Sweden. "In the summer of 1996, I discovered a second-hand record shop in Stockholm with a large sign saying 'sale'. When CDs took over the market in Europe, many people wanted to get rid of their old records and sold them below their value. For me, that was fantastic!" The first record that Zhang bought in Europe was "I'm Your Man" by Leonard Cohen. "I told him without being asked that I had come all the way from China and that I absolutely had to have the album," he remembers, laughing. Many thousands more were to follow, so many that he can no longer count them. "Soon I wanted to have all my favorite albums on vinyl. Beatles, Rolling Stones, David Bowie." He didn't have a record player back then either. "I didn't have to play the albums anymore. I had internalized the music, I could hear it anyway, in my head."

In the 90s and 00s, Zhang made many more trips around the world to visit festivals and discover new music. "I often acted as if my hand luggage was really light, but it was full of heavy records." Sometimes he traveled with an empty suitcase and packed music that was still almost unknown in China, such as the pulsating prog techno of Underworld, which Zhang had discovered through the soundtrack of "Trainspotting". "I found it really impressive that dance music DJs in Europe at the time only played vinyl. This old medium for such futuristic music! I was also fascinated by the whole culture around it and started buying more and more dance LPs myself. From being a radio DJ, I slowly became a rave DJ with two turntables and my own series of parties in Beijing." Zhang suspects that for several years he was probably the only person in China with a modern, international record collection. "For me, vinyl is like a time capsule. I have music that I love on cassette, CD and vinyl. But I haven't actually listened to all of it in all formats yet. I'll do that when I retire."

"Today there are two types of collectors in China," says Shi Jing, who runs one of the country's largest online vinyl forums, "Diggers Delights." "Some are collectors who mainly buy classical music or expensive special editions of albums that they consider to be classics. The others are real diggers, constantly on the lookout for something new." The 42-year-old is one of the few pop scholars in China. With "The Bible of Hip Hop," he has written a standard Chinese work on hip hop culture. His second book, a guide to funk and soul music, will be published soon. Books are piled up in Shi's home in Beijing. The devout Buddhist has set up a shrine in front of the shelves that take up the entire wall. The sanctuary with incense sticks and a golden Bodhisattva watches over around 4,000 LPs, which he also had to painstakingly collect over years. Most Diggers, like himself, come from the "Dakou" generation, says Shi. "Around the time MP3s came along and nobody wanted CDs anymore, they came across vinyl and thought, oh yeah, there's still something to collect."

Shi bought his first record around ten years ago, a good five years before the vinyl hype started in China, "simply because the cover looked great." At that time, most buyers didn't bother with records. "That's why you could still get real bargains back then," says Shi. "I remember buying a Smiths record for just 30 RMB (about 3.80 euros) about seven or eight years ago. Or John Coltrane for 40 RMB. Or two Fela Kuti box sets, each for 41 RMB. Crazy." Xiao Bing felt the same way. "Five or six years ago, you could still get fantastic vinyl collections online on e-commerce sites like Taobao for very little money. Then at some point a friend showed me Discogs and I began to appreciate the value of records on the international market. It was astonishing. I felt a bit like I was suddenly trading on the stock market." Her rarest item is a Japanese fusion rock record that she bought for 20 RMB, the equivalent of 2.50 euros. "Nobody was interested in the record back then. Today it is a sought-after item and is worth 2,000 US dollars on Discogs." Shi confirms: "In the past, vinyl dealers had no idea what they were selling. Today they look very carefully at what they buy and import." He pauses, takes off his glasses and laughs: "But let's not talk about quality. In China, every record is immediately classified as 'near mint'. In that respect, things are not very professional yet."

Vinyl has only been produced locally in China for about five years, in three newly opened pressing plants in Shanghai, Shenzhen and Guangzhou. "Big record companies like Universal and Sony have their products produced here. That makes it easier to get the license for the Chinese market," says Zhang. "Many albums by Western and Chinese pop stars are now often released on vinyl in small quantities," confirms Xiao Bing. "It may not be the best quality in the world, but it is certainly not the worst either."

In addition to the large pressing plants, some of which have long waiting times, there is a scene in China of semi-legal lathe-cut producers such as HakHak from Shenzhen or Qiii Snacks from Guangzhou. They mainly serve small, independent labels. For the underground scene, vinyl offers a welcome opportunity to earn some money in the precarious music market. Hardly anyone buys CDs in China anymore. Streaming brings in even less than in the West. Bands make profits - just like here - mainly through concerts, merchandise and also records, which are often very elaborately designed. Xiao Bing included a perfume sample with one of her releases, a white vinyl edition limited to 150 copies by the electronic producer Knopha. The specially composed scent is intended to merge with the ethereal ambient music to create an overall experience. Even if the "Made in China" brand still has a junk image around the world - when it comes to vinyl, you get value for your money in the Middle Kingdom. However, producing records locally is still not the most popular option due to the costs, risks and bureaucratic hurdles. Many labels prefer to have their releases pressed abroad, even if that means having to accept problems with import.

"As long as you keep the numbers small, you won't be the focus of attention," explains Nevin Domer. He speaks from long and often painful experience. Eight years ago he founded China's first DIY vinyl label, "Genjing Records." The 39-year-old is also a legendary figure in China's rock underground. The pierced but otherwise rather inconspicuous American came to China to study in 1999. After an interlude in South Korea, he has lived in Beijing since 2005, where he organized foreign tours for local bands such as PK14 and Joyside as part of "Maybe Mars" - the most important label for alternative music in China alongside "Modern Sky." As a booker for the legendary but now closed "D-22" club (featured in the rock documentary "Beijing Bubbles," among others), he also brought top-class bands to the Middle Kingdom. He started his own label "Genjing Records" in 2011 as a passion project in the spirit of the DIY spirit with which he was socialized in his hometown of Baltimore as part of the hardcore scene. "Genjing", which roughly translates to "spurs", specializes in split singles that bring Chinese and foreign bands together. The idea came out of necessity. "In 2006, I played in a hardcore punk band in Beijing called Fanzui Xiangfa (translated: "Dangerous Thoughts")," he tells us in a small theater café near Beijing's tourist mile "Nanluoguoxiang". "We wanted to tour internationally, through Southeast Asia and Europe. Even back then, you couldn't make any money from recordings in China. But we knew from musicians like Yang Haisong (PK14) that a lot of people abroad buy vinyl to support you. In the underground punk scene in the West, vinyl never really went away." Domer's plan was to record a split single with a band friend from Malaysia especially for the tour. "But I couldn't find a label in China that could produce records, and our lyrics were too political, so it soon became clear to me that I would have to take matters into my own hands."

Domer used his network of contacts in Europe and the USA to press the record. Because he soon realised that you would be noticed more quickly by promoters, bookers and critics if you offered vinyl at the merch stand in China, he soon offered his services to other bands in the scene. "For many of us, our records were mainly collector's items. Only a handful of young people actually had a record player at home," Domer remembers. So at the beginning he sold the devices as well. "Portable devices with batteries and built-in speakers from Guangzhou. The quality was really bad. I quickly gave up on it," he says, laughing.

To date, "Genjing" has released around 50 split/inches with a quantity of 500 copies each, even though Domer, as a child of the CD generation, doesn't really have a special relationship with vinyl, as he says. The fact that he has nevertheless contributed to the vinyl trend in China with "Genjing" fills him with pride. "For the last two years, my domestic sales have finally been growing. That's very satisfying to see," he says. His limited, beautifully presented collector's items, including those with well-known Chinese bands such as Demerit, Duck Fight Goose, Round Eye and Snapline, have become increasingly popular internationally over time. "I have three to four orders a week, for example via Bandcamp."

Domer has the majority of his releases pressed in the Czech Republic and the USA. They are stored in a small depot near LA, from where a friend sends them to customers and record stores all over the world. Producing locally in China is hardly an option for Domer. "It's difficult for me because many of the bands on the split singles come from abroad. They can't easily go through the state licensing process in China. They don't have the identification numbers and all the bureaucratic stuff that you have to submit."

He usually sends the copies that are intended for China via the special economic zone of Hong Kong, where there are no import taxes and Chinese censorship of cultural goods does not apply. From there, other friends then distribute them in packages for onward shipment to mainland China. "That way, only small numbers of items get stuck in customs." Since Xi Jinping came to power, controls in the country have increased, says Domer. "What comes in is checked much more strictly and effectively. In the past, you might have to pay additional taxes, but today, if you're unlucky, the goods are immediately destroyed." Zhang Youdai has had similar experiences: "In the past, they would wave you through at customs or at most make jokes about the 'all the rubbish' you had in your suitcase. Now you get into trouble if you bring too many records with you. But it's my job to introduce them to people!"

When Xi Jinping came to power in 2013, a new ice age began for civil society freedoms. This also affects cultural life. No country has ever invested as much money and manpower in the censorship apparatus as China does today. Nowhere else are there as many surveillance cameras as here. On the Internet, critical opinions are now filtered out with the help of artificial intelligence. In public, people have gotten used to self-censorship. If you don't stand out, you can live a good life in China. However, other perspectives, especially those from the West, are closely scrutinized. Only 34 foreign films are allowed to be shown in cinemas in China each year. Concerts by foreign bands are only permitted if they submit their texts and videos to the authorities weeks in advance and, if necessary, remove "sensitive" content from the program. There are always last-minute cancellations. Everyone who moves outside the mainstream in China is fundamentally paranoid.

"I was once pulled over at the airport and had to tell the officials what the contents of the records in my suitcase were," Domer recalls of a tricky case. One LP in particular, a split release for the noise bands Torturing Nurse and Primitive Calculators, caught the attention of the customs officers. The cover shows two applauding communists in Mao suits - with cut-out faces and banal newspaper clippings pasted over them.

"The officers must have looked at the cover for 20 minutes and then looked for the band online. In the end, they even listened to the music - brutal harsh noise! And they did it without batting an eyelid, while I stood nervously by," says Domer. He still laughs nervously about the episode. "Of course, I didn't mention that I produced the record myself. I explained that it was a gift for a friend." In the end, the customs officers came to the conclusion that the cover in particular was "inappropriate for China": import refused.

All the effort, the game of hide-and-seek and the search for loopholes, is of course reflected in the price. "I estimated around 200 RMB (around 26 euros) per LP, mainly because of the shipping costs," says Domer. But he still doesn't make any money from it. "I'm more likely to lose some." For niche label makers like him, the vinyl business is primarily an idealistic hobby. "I come from a DIY underground scene. The bands I release are my friends. I can support lots of different musicians, which makes it interesting for me." You can't really grow with it. In China, the bigger you get, the more adaptable you have to be. "I try to keep my head down and not attract too much attention. I'm also very cautious with political content," says Domer. The fear, fuelled by uncertainty, that it could potentially affect anyone is calculated. There is a saying in China that fits well: "Kill the chicken to scare the monkey" - if you get too big and too loud, you may be made an example of. "I was often afraid of losing all the records I had carefully collected and having to pay a fine on top of that," says Zhang Youdai. But none of them want to stop. "Putting all that on the line is still better than pursuing a job you don't like," says Xiao Bing.

_____________

Turbulent times

Despite all the hassles and hurdles that music lovers and record producers have to endure in China, it is still not a return to Maoist times. The history of vinyl in China actually began long before music enthusiasts started digging discarded records out of the trash in the 1990s.

The first shellac records, which were intended for export to the Chinese market, appeared as early as 1903. Companies such as Beka, Victor, Columbia, Odeon and Pathè hoped – just as they do today – to reach millions of potential customers in China. Even before the fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911 and the transition to a republic, the country had opened up to Western ideas and innovations – out of necessity: after the British forced China to open up by force of arms in 1874, other colonial powers soon followed in order to continue to bleed “the sick man of Asia”. “As long as we cannot beat the imperialists, we should at least learn from them” was the motto of many Chinese intellectuals. This had already worked well in Japan, which, after a rapid modernization process, had even beaten Russia in a war. Music was an integral part of this learning process. Education politicians trained in Germany such as Xiao Youmei, Wang Guanqi and Cai Yuanpei were of the opinion that the German Empire was able to catch up with the other great world powers so quickly thanks to the power of music. The first surviving Chinese writings on music already referred to the close relationship to good government. For Confucius, music was one of the most important means of ensuring the moral education of citizens. Under these premises, China's large coastal cities became laboratories of modernity in the 1920s. A basic knowledge of classical music, jazz, ballroom dancing and marching music soon became de rigueur in the upper classes of society. In Shanghai, the cosmopolitan "Paris of the East", there was one of the best orchestras in all of Asia, conducted by the Italian Mario Paci, who had studied at the conservatories in Naples and Milan. Gramophones, first introduced in China around 1890, were also omnipresent in the pleasure-loving city in the 1920s.

The first record factory in China was opened by the French record company Pathé-Orient at the beginning of the 1920s on the edge of the French concession in Shanghai. The factory, which had already faced competition from the Japanese-Chinese joint venture "Great China Records" in 1923, produced a good 300,000 records a year. It was not just Western music that was circulated: fueled by the emerging radio and a still young film industry, Chinese titles soon became the main business, including folk songs, pieces from the Peking Opera and so-called "sing-song music" sung by Chinese courtesans, some of whom dominated the headlines of the daily press with their love affairs and fashion extravagances - influencers of their time.

The Sino-Japanese War from 1937 to 1945 and the subsequent civil war put an end to the Republic's cosmopolitan heyday and with it the boom of the Chinese record industry. When Mao Zedong proclaimed the People's Republic in Beijing's Tiananmen Square in early October 1949, music production was not over. In May of that year, the communists had already occupied the "Great China" factory in Shanghai and produced seven new recordings that were to provide the soundtrack to liberation, including titles such as "The Army Marches Forward" and "Heaven in the Liberated Areas". For the Great Chairman Mao, any kind of art was a means of educating the masses and sowing an awareness of the class struggle. Under the communists, the production facilities were nationalized, and the old record companies were absorbed into the "China Record Corporation" (CRC), which, like "Amiga" in the GDR, held the state monopoly. Supposedly outdated, "feudal" musical traditions were increasingly replaced by revolutionary songs, which made up almost the entire repertoire. During the Cultural Revolution, which raged between 1966 and 1976, the hunt for "old evils" finally degenerated into hysteria. Traditional songs, hits from the republican era and western performers were branded as "decadent", "revisionist" and "imperialist". Possession of western instruments, western clothing or foreign diplomas was enough to be exposed as a "right-wing deviant" or spy. At the Shanghai Conservatory alone, 18 music teachers took their own lives in the first few months after the start of the Cultural Revolution. As an alternative to the "bourgeois" sounds, Mao's wife Jiang Qing invented the so-called "model operas", ideologically purified dance dramas full of revolutionary heroes and insidious enemies of the proletarian revolution. Henry Kissinger, who as US security advisor had the pleasure of hearing such an opera during Nixon's legendary state visit in 1972, described it as an art form of "stupefying boredom": "The bad guys wore black, the good guys wore red, and as far as I could tell, the girl fell in love with a tractor at the end," he says in one of his memoirs.

In the midst of the many purge campaigns, it could easily happen that the wrong records in the cupboard became a matter of life and death. Collectors burned their valuable old pieces or buried them in the garden in the hope of better times. "In my youth, listening to music was a secret," Mr. Gu remembers of the turbulent times. The slim 72-year-old has experienced all the highs and lows, all the hopes and disappointments that China went through in the 20th century first hand. In 1947, two years before the founding of the People's Republic, he was born into a cosmopolitan family amid the turmoil of the civil war. His father was a bank employee, his mother a teacher. "My parents loved the Peking Opera. My brother, who was eleven years older than me, loved going to dance balls. Back then we called it 'light music'," the classical music lover tells us in a café on North Shaanxi Road, once one of the chicest nightlife streets in old Shanghai. "Before the Cultural Revolution, harmless pieces, such as traditional operas, were still allowed. After that, the only music that was allowed was that which was composed for the 'liberation of the people'," says Gu. "People didn't dare play the old records anymore. At home, they slowly got moldy in the basement."

During the Cultural Revolution, Gu, then in his 20s, worked for the state-owned China Record Corporation. "I was a master printer in the factory where the record covers were made, and also a member of the propaganda department." For our conversation, Mr. Gu brought along some of the old record sleeves that were made in his work unit at the time: beautifully decorated paper sleeves with classic Chinese ink painting and the CRC logo with Tiananmen Gate and Dragon Column. To our surprise, some of them are labeled in English. Gu explains why: Similar to Mao's Red Book, many of the records were also sold abroad through a state propaganda publishing house - "for the liberation of the proletarian peoples worldwide."

Like for many Chinese of his generation, the Cultural Revolution was a formative experience for Gu. On the one hand, he wanted to belong and was passionate about the cause, but on the other hand, he knew that he could be criticized as a "capitalist" at any time - especially with a family background like his. "The party's strict controls also extended to parents and grandparents. They said: 'Only upright roots produce red shoots,'" Gu remembers, adjusting his intellectual glasses. Alert, cheerful eyes flash behind the thin frames. It was all a long time ago, and yet you can still see the young man who always loved music more than anything else and learned early on to make the best of his circumstances. The often unattainably high political standards of the "Red Guards" could not stop him from continuing to listen to forbidden music. "As a member of the propaganda team, I had free access to the media room. There I found hundreds of records. Most of it was to the taste of the workers, revolutionary music and patriotic operas, not quite my taste," says Gu. "But you could also find compositions with romantic love as the main theme or western operas like 'La Traviata'." Since it was forbidden to play these records, it didn't matter if they were missing, says Gu, grinning mischievously. He and a colleague secretly took the forbidden records home with them to copy them via the output channel of the record player. "You could still buy blank tapes back then, even if they were very, very expensive. But one tape could hold a good three hours of music." At home they played the tapes quietly and only with the windows closed. Sometimes friends came over, artists who wanted to paint to the sounds of classical music. This went well for a while. Until one day "a small accident" happened, as Mr. Gu puts it. "Once, in a hurry, we accidentally took a Shanghai Opera record from the office. A member of the radio team had a soft spot for this music. That's why she noticed that a record was missing. Shortly afterwards, we were exposed and publicly pilloried as 'glorifiers of feudalism' and 'sons of capitalists.'"

There is no resentment in Mr. Gu's voice as he talks about that dark time. His country's history is also his history, and the fact that China has come so far since then fills him with pride. "Ideology has always been at the center. But China has changed, society has modernized. Today the government no longer prevents diversity in music."

After Mao's death and the conviction of the "Gang of Four" around Jiang Qing, who were blamed as scapegoats for the Cultural Revolution, China actually opened up at the end of the 1970s. The rehabilitated reformer Deng Xiaoping demanded that all the people's efforts should now be judged on their contribution to the modernization of the country. This also applied, to a certain extent, to cultural life, which was no longer completely isolated from the outside world. "After the Cultural Revolution, things moved quickly. Relatives brought cassettes of singers like Teresa Teng (a crooner from Taiwan - author's note) from Hong Kong. But people still listened to them in secret. People weren't quite sure whether they could trust the stuff," remembers Mr Gu.

In order to convince the people at home and the world outside of the modernization intentions, the Chinese Ministry of Culture dared to make a coup in the early 1980s that could hardly have been more modern: just one year after the show trial of Jiang Qing, Jean-Michel Jarre was allowed to perform in China in 1981 as the first Western pop musician ever. The long-haired Frenchman arrived with 15 tons of stage equipment. In a dandy white suit, he played five stadium concerts, entrenched behind expansive keyboard castles, while the colorful rays of a laser light organ danced in the lenses of his sunglasses. "This show would have been futuristic in London, Paris or New York, but in China at that time it was almost as if an alien had landed," Jarre recalled years later.

Mr. Gu was one of the lucky ones who was able to experience the alien from the West up close. Through his work unit at the state record company, he had managed to get a ticket for the Shanghai concerts. "We had never seen anything like it before. So many bass boxes, probably 10 to 20 on one side alone. And all the cables on the floor!" Jarre, who had paid for the tour out of his own pocket, even allowed the Chinese to press his music on record without royalties. "That will open up the market for us," his PR agent explained to "Spiegel" after the tour. "Back then, Western culture was gradually coming to China," confirms Mr. Gu. "It was as if the windows to the world had been opened, but not the doors."

Unfortunately, soon after the Jarre concert, the windows closed again for a while, apparently along with the curtains. Around 1983, the party hardliners, who had been panicked by so much desire for reform, regained the upper hand. A campaign against "intellectual pollution" and "cultural contamination" was launched. Bans on performances for Chinese artists became commonplace again. Foreign musicians only came to the country very sporadically. Records were also over. In the 1980s, when there was no longer a market for old-fashioned "red" music and CDs came along, the pressing machines were sold abroad, especially to Japan. "It was not until the end of the 1980s that it was possible not to be afraid when playing foreign music," says Mr Gu.

He has heard of the "Dakou" records that came to the country a little later. "But I don't know much about them." Does he still listen to the old records often these days? "No, hardly any more," he says, stirring his coffee absentmindedly. But with all the stories from the past, some memories come flooding back. "I should get a tape machine again," says Mr. Gu. "To bring the old tapes from back then back to life."