China’s urban exodus: The renaissance of the “beautiful villages”

"This is heaven on earth," says Zhang Jinglei about her new home. The filmmaker had lived in China's capital Beijing for ten years. Ten months ago she packed her things and moved to Caicun, a suburb of the city of Dali in Yunnan Province, a good 2,000 kilometers away. In just a few days, the 32-year-old found a two-room apartment for 1,000 yuan in the village dominated by the Bai minority. In Beijing she had paid three times as much - for a room in a shared apartment.

The desire to leave Beijing had been growing in her for some time. In the city, the only way to escape the social pressure was to go out and have fun and drink alcohol. "I had to make the jump," she says. Zhang, who was born in the metropolis of Tianjin with its 14 million inhabitants, says her life is now easier. She has adopted a dog and even a pig, which she now walks on a leash.

Everyday life with a domestic pig and a dog: Like former city dweller Zhang Jinglei, many young Chinese dream of a simpler life in the countryside

Although the Chinese state has been promoting urbanization for decades, a reverse migration movement has also started. Real estate prices in urban areas have become unaffordable, especially for young professionals, and competition for school places in popular neighborhoods is nerve-wracking. In addition, the middle class has a new awareness of physical and mental health. During the Corona pandemic, many Chinese also discovered the diversity of their homeland. According to the Chinese travel portal Trip.com There have never been as many road trips in China as in the past two years. Outdoor sports and camping have also never been more popular in the People's Republic.

Zhang says that other city dwellers who turned their backs on the urban madness during the pandemic live in her house in Caicun, including a former Huawei employee. Many young people who move to the countryside initially “lie flat” – “Tangping” – “躺平”, a buzzword that Refusal attitude of young Chinese who, instead of striving for a career, family and possessions, only do the bare minimum to make ends meet (China.Table reported). But after a period of acclimatization, many would want to do something. "Bake bread, open a bar or sell art on the street."

The state welcomes the new exodus from the cities. In 2017, President Xi Jinping first spoke of his strategy for "rural revitalization." Small farmers will continue to be replaced by large agricultural companies, but there are also newer initiatives to promote medium-sized, organic farms. Another goal is to expand the infrastructure with schools, clinics, housing, roads and railway networks. Life in the countryside should become so attractive that young city dwellers will also move their lives there.

"There are many attempts to revitalize rural areas with young talent," says Elena Meyer-Clement, professor of China studies at the University of Copenhagen. One of her main focuses is research into urbanization, administrative and land reforms in China's rural and semi-urban regions. Entrepreneurial initiatives and tourism are specifically promoted by individual local governments, she says. "It's a trend that can also be seen in almost all other post-industrial states, be it Japan or Brandenburg in Germany."

What is special, however, is that the process in China is taking place at the same time as rapid urbanization - "almost like a kind of top-down population exchange," says the scientist. To put it bluntly, small farmers are supposed to migrate to the cities to promote domestic consumption there, while young, educated city dwellers are supposed to bring new, creative ideas to the countryside to make the economy there more socially and ecologically sustainable.

“Beautiful villages” as economic drivers

This includes the so-called "beautiful villages," says Meyer-Clement. "For this, existing villages are renovated or completely new ones are created that look like spruced-up traditional villages." One example is the small town of Longtan, which, with its stream and mill wheel, nestles picturesquely in the mountainous landscape of Guangxi Province. It is said to be 400 years old, writes the local government, which is promoting the influx with a budget for art projects and renovation work.

The Feng Shui is evidently correct: 200,000 tourists come to Longtan every year to admire the Qing architecture or watch plein air painters at work. Even the older villagers were trained here as artists who now sell their work to tourists. "Many of these creative rural residents have Douyin channels, the Chinese Tiktok, on which they demonstrate how simple but also modern life in the countryside can be," says Meyer-Clement. "Young, dynamic, creative plus traditional values that have been lost in the city."

However, the trend can only be observed in isolated cases and is limited to more developed areas, particularly on the east coast of China. "Absolute poverty has only just been overcome. Artist villages are not yet a big issue," says Meyer-Clement. "Things like e-commerce already work very well in rural areas. However, I doubt whether such beautiful villages are a sustainable strategy."

The new rural residents see things differently, of course. Shen Lan is one of them. Shortly before Shanghai went into its first major lockdown, the author and cultural scientist moved with her husband to an artists' village outside Liangzhu in Zhejiang Province. The landscape, characterized by mountains and rivers, is closely interwoven with Chinese cultural history. People already settled here several thousand years ago.

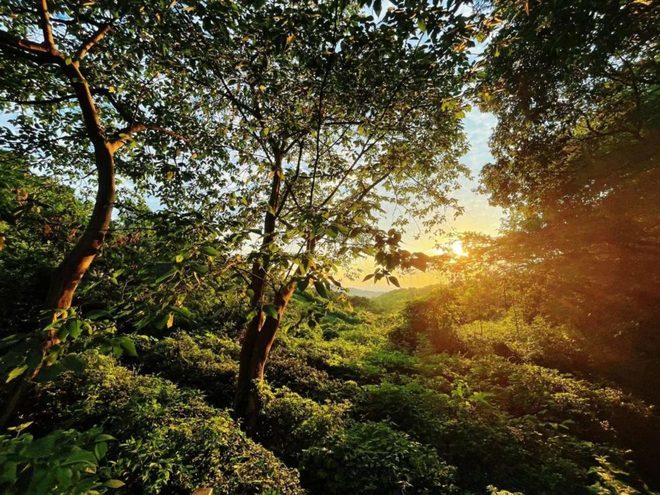

Shen is working on a book about Chinese natural philosophy, hermitage and art in the picturesque surroundings. In the mornings, she often climbs a hill ten minutes from her house and watches the sunrise. There are other dropouts like her living in her village, a writer, a professional dancer and a professor of anthropology. The atmosphere is very familial, she says.

Shen had lived in Shanghai for seven years, in a spacious apartment near the Jing'an Temple, with a small garden in the backyard. Nevertheless, she did not find what she was looking for in the city: balance and spirituality. For Shen, life in the country is closely linked to the philosophy of tiān ren hé yi (天人合一), which the philosopher Zhuangzi, for example, represented: Man is part of nature. Heaven and man are originally one. The goal is the harmony of all elements. "We Chinese have a very deep connection to nature, it is in our blood," says Shen. Even the ancient Confucians had the dream of retiring to the country when they had done their duty in the world.

Of course, worldly factors also play a role for Shen. In Liangzhu, she and her partner live in a 140 square meter apartment for just under 4,000 yuan. The internet connection and infrastructure for everyday things are also excellent. "You can order food online or buy at markets or directly from the farmer," she says. "Here, we can combine a traditional lifestyle with modern amenities."

Their long-term goal is to live in an even more environmentally friendly and sustainable way and perhaps one day to establish an eco-settlement themselves. "It's as if we are returning to our roots. With a greater awareness of nature, of life and of who we really are."

Collaboration: Renxiu Zhao